Betting markets give Zohran Mamdani a 1 in 3 chance of winning next week’s Democrwatic primary for Mayor of New York City.

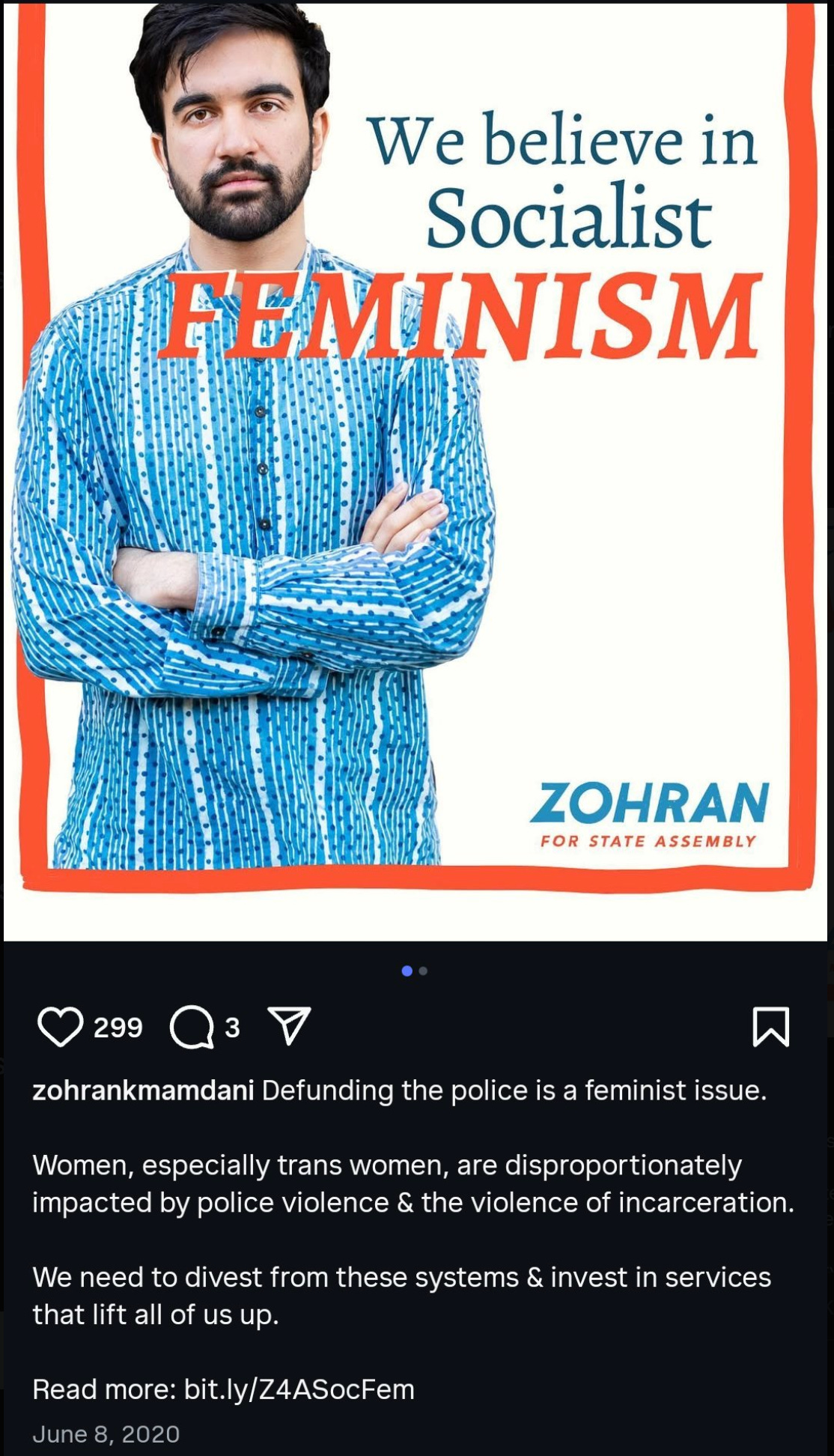

Which means Democrats may not have long to prepare comments on posts like this:

Defunding the police is a feminist issue.

Women, especially trans women, are disproportionately impacted by police violence & the violence of incarceration.

We need to divest from these systems & invest in services that lift all of us up.

The Anti-Endorsement

The New York Times editorial board issued a ‘withering’ anti-endorsement of Mamdani today, saying he is unqualified and "is running on an agenda uniquely unsuited to the city’s challenges".

Mamdani is a Two-Wiki kid: both his parents are famous enough to have Wikipedia entries. Tuition at his middle school will set you back $68,793, he went to Bowdoin. He’s got the perfect 2020s socialist resume.

Hell, lets go to Wikipedia for the full work resume. Most commonly marked by the word “unsuccessful”:

After leading student organizing campaigns, Mamdani became involved in politics. In 2015, he volunteered for Ali Najmi’s unsuccessful campaign in the 2015 special election of New York City's 23rd City Council district. In 2017, he joined the Democratic Socialists of America, and worked for the unsuccessful campaign of New York City Council candidate Khader El-Yateem, a Palestinian Lutheran minister and democratic socialist running in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. Mamdani was the campaign manager for Ross Barkan's unsuccessful bid for New York State Senate in 2018. He also worked as a field organizer for democratic socialist Tiffany Cabán's unsuccessful 2019 campaign for Queens County District Attorney. In October 2019, Mamdani announced his campaign for New York State Assembly …

Fast forward to today, and Mamdani trails Andrew Cuomo by double digits in both recent public polls, roughly 36% to 22%. But the Ranked Choice Voting system in the NYC party primary gives him that 1-in-3 lane to the nomination, as the progressive left falls in line co-endorsing him.

And because of NYC’s quirky election rules - there is no Ranked Choice Voting in the general election, but losers of the primary election are eligible to run on other party lines - all hell could break loose. The general election field could include the socialist Mamdani as the Democratic nominee, Andrew Cuomo on another party line, incumbent scandal-plagued Mayor Eric Adams as an Independent, and the Republican nominee, who received 28% last time.

And it could take days to determine the primary winner.

Phrases like “defund the police for feminist socialism” and “New York City” and “weeks of vote-counting” and “all hell breaking loose” guarantee a media frenzy leading up to the general election on November 5th.

A nightmare for national Democrats.

But Democrats don’t need another unnecessary nightmare right now, so let’s make this about democracy reform and partisan faction building.

Annie Lowery, writing in The Atlantic, has sparked a conversation on how much blame to assign to RCV for the confusion:

Seeing a no-name upstart attempt to upset a brand-name heavyweight is thrilling. But the system has warped the political calculus of the mayoral campaign. Candidates who might have dropped out are staying in. Candidates who might be attacking one another on their platforms or records are instead considering cross-endorsing. Voters used to choosing one contender are plotting out how to rank their choices. Moreover, they are doing so in a closed primary held in the June of an odd year, meaning most city residents will not show up at the polls anyway. If this is democracy, it’s a funny form of it.

I don’t think this is quite right. Lowrey’s argument is worth engaging with, but the more revealing development is what hasn’t happened as RCV took hold in NYC over the past five years.

Is it RCV’s fault that centrists did not adapt to the rules change as well as progressives?

Electoral Reform + Faction Building

Over the past decade, an electoral reform movement boomed as a structural way to address the dysfunctional polarization of American politics. An effective entrepreneurial ecosystem formed, as a network of academics, entrepreneurs, and philanthropists built a coherent field with Ranked Choice Voting as its most prominent intervention.

From ballot initiatives to whitepapers to conferences, “reform” became a thing. I hopped on the bandwagon early, and remain attracted both to the ideas and the impressive community that has built up around them.

In recent years, my engagement has been limited to the Welcome perspective: reforms are good, but may fall flat without strong partisan factions. So I’ve often framed partisan faction building as complementary to structural reform initiatives.

But the NYC mayoral election is a high-profile example that complementary may understate the case.

Is partisan faction-building not just complementary to electoral reform, but necessary for its success?

There is no “The Democratic Party”

The most common question our team gets is “But doesn’t the Democratic Party do that?”

We started writing this newsletter in no small part to explain they “the Party” doesn’t do tons of the things you’d think a party would do - especially make strategic decisions & investments.

While “the Democrats” are an amorphous blob of individuals and institutions (politicians, political committees, party committees at all levels, think tanks, media outlets, organizing and advocacy groups, etc.), the progressive left faction is a real thing.

And we are seeing that in NYC right now. The progressives are an organized partisan faction, so they can exert coordinated power even though the winds are blowing against them nationally.

Josh Barro captured how the lack of an organized centrist faction is missing an opportunity in NYC in his recent piece The New York Mayor’s Race Sucks. While there were multiple strong centrist candidates in the last NYC mayoral election …

In the ensuing four years, the national “vibe shift” has pushed big-city politics to the right. You would think this year’s Democratic mayoral primary, also using ranked choice, would be even more favorable ground for moderate candidates than the last one. But there’s a problem: This time, nobody quite like Garcia is running, which means a lot of voters, including me, are pretty annoyed by this field.

Indeed, in this year’s nine-candidate field, there’s only one candidate who even says he voted for Garcia. That’s Whitney Tilson, a former hedge fund manager who helped to found Teach for America, and who has sensible, Garcia-like ideas about how he’d run the city.

Progressives have multiple candidates who are now all cross-endorsing each other. Because leftists have an organized faction, they are able to adapt to rules changes. Here is Grace Segers writing in The New Republic on how progressives in NYC responded to moderates winning the first election with RCV, in 2021:

In an effort to understand the victory of moderate Democrat Eric Adams, who has been embroiled in multiple scandals during his four years as mayor, the New York Working Families Party—a powerful progressive party organization in the city—began analyzing how they might ensure a candidate more favorable to its ideals could win in 2025.

“Despite the skepticism at the time of ranked-choice voting and how voters would understand and engage in it, the fact is that most voters gave it a try. But the political ecosystem of candidates, of endorsing organizations, press, and elected officials, for the most part, didn’t actually try to guide voters how to use ranked-choice voting,” said Ana María Archila, co-director of the New York Working Families Party.

…

“We spent a lot of time looking at that to understand, what are the pieces that need to be in place?” said Archila. “We need to create an ecosystem that supports collaboration instead of just competition. We need to endorse a slate of candidates and help them work together. And we need to make sure that voters are told, very explicitly, not to rank the candidate of the opposition, which in this case now is Andrew Cuomo.”

Progressives adapted to the rule changes, an expected dynamic we detailed in Centrist School II: Learning From The Far-Left. With an organized network in place, progressives spent the years between 2021 and 2025 responding to the RCV world and were prepared to incentivize candidates to consolidate voters against a candidate in the stretch run.

Centrists, without a comparable ecosystem, have been left flat-footed.

The past decade of studying the progressive ecosystem (and often losing to it!), has hammered home certain truths. Chief among them is that while today’s formal parties are slow and weak, organized political factions are nimble and powerful.

Democrats, and democracy, would benefit greatly from more robust factions of partisan centrists.

So would democracy reform.