The Declining Value of a (Political) Dollar

Election analytics superstar Lakshya Jain on the shrinking and changing value of money in politics.

In our search for the best high-ROI opportunities for Democrats, we’ve been learning from the team at Split Ticket, whose analysis has guided and challenged our thinking about what’s possible in our polarized era.

In a particularly notable post from April of last year, Split Ticket partner and “Election Twitter” mainstay Lakshya Jain explored “The Declining Value of a Dollar” in contemporary campaigns and elections.

The basic argument is that rising polarization at the partisan fringes in recent years has made a state’s presidential lean a better predictor of its Senatorial election outcomes than the amount of money spent by the parties. In other words, “as the significance of partisanship has increased, the significance of money has decreased.”

But as Lakshya notes, this does not mean that voters are immovable or that seats are unflippable by way of increased investment:

This is not to say that money does not matter. On the contrary, estimates done by Split Ticket and by other independent sources have found that financial spending still does move the needle noticeably…

This ties into our own view of the opportunities and challenges of modern politics.

As polarization rises at the fringes, the fact that we can still move the needle to put the shrinking but still significant crop of seats in the middle into play becomes all the more important. As the value of a dollar decreases at the fringes, it becomes even more valuable to invest in the battlegrounds where a relatively small share of movable voters could flip a seat — and control of a narrowly-divided Congress.

In our quarterly “Conceding Democracy” reports, we’ve highlighted undervalued seats where Democrats could potentially compete to win if they invest enough in candidate recruitment and support. We’ve called out the irresponsible influx of Democratic dollars to unwinnable fantasy campaigns like Marcus Flowers’ doomed bid to topple Marjorie Taylor Greene and suggested those dollars be sent to districts where they can move the needle. And we’ve elevated the profiles of candidates like Boebert challenger Adam Frisch, who can put those seats into play.

With Lakshya’s permission, we are re-posting his essay from April, 2021. While the piece is a year old, it has only become more relevant. Since the time of its publication, the 2022 cycle became the most expensive midterm cycle in history — notching $9 billion spent across all parties and candidates — while the overall share of competitive House seats was further reduced through the decennial redistricting process.

Check it out below and don’t forget to subscribe to Split Ticket!

The Declining Value of a Dollar

By Lakshya Jain, Split Ticket

I need a dollar (dollar), a dollar is what I need…

And if I share with you my story, would you share your dollar with me?

The lyrics above are really to the 2010 Aloe Blacc song “I Need a Dollar”, but they might as well be from a desperate text sent by electoral candidates and political parties on the eve of an election. Every cycle comes packed with panicked calls and messages from candidates begging for donations to hit an arbitrary, undisclosed financial threshold. Each time, donors and supporters open their wallets, allowing political parties to set new spending and fundraising records with incredible frequency. And yet over each of the last four election cycles, the relative importance of the dollar has declined.

Through data from OpenSecrets, we can see that the inflation-adjusted amount spent on congressional elections alone has increased in every cycle from 2014 onwards, culminating in a stunning $8.7B spent in 2020. In fact, the 2020 cycle had the five most expensive and eight of the ten most expensive congressional races in history (the other two were from 2018).

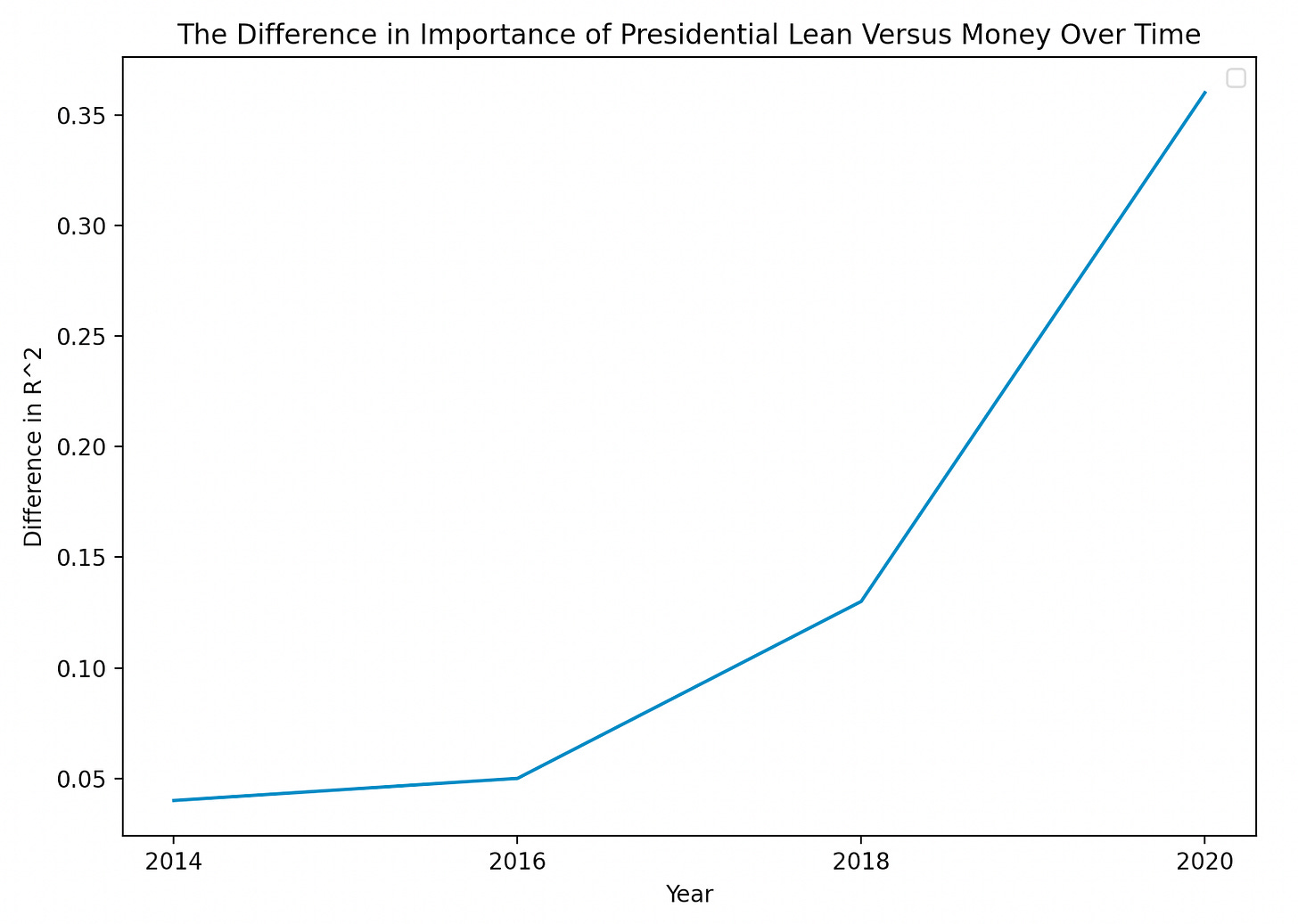

Surprisingly, however, the spike in spending has also been accompanied by a precipitous decline in its influence; as the importance of partisanship has risen, the significance of the dollar has dropped accordingly in elections. This can be seen by examining the impact that spending and presidential lean have had on Senate elections over the last four cycles, after controlling for incumbency. Modeling done by Split Ticket allows us to visualize the isolated importance of both relative partisan spending and presidential partisanship and the change in significance that these factors have seen over time — the result is displayed below.

The graphic shows how in 2014, a Senate forecast that only used campaign spending would have done almost as well as a forecast that only relied on a state’s presidential lean, because money and partisanship were nearly equal in predictive significance. But by 2020, a forecast based on presidential lean would have performed significantly better overall. Moreover, the money-based forecast would have done significantly worse in 2020 than in any other prior cycle, despite spending being at an all-time high.

The graph above also shows that the difference in importance between partisanship and money has grown in every single cycle from 2014 onwards, and that it was highest in 2020. If we visualize the difference in importance between the two factors over time, this becomes exceptionally clear.

One reason for this may simply be because both parties are awash with cash, and so being outspent might not matter as long as they have enough money to put their message out. The other reason likely has to do with increased polarization, fueled by mass media. With the amount of swing voters declining year-over-year, the number of “strong partisans” has risen sharply. Strong partisans are, by definition, far less likely to switch parties than any other group of voters. It should come as no surprise, then, that as the pool of persuadable voters dwindles, the relative impact of spending would also shrink, as there are simply less voters to sway.

We can see evidence of increasing partisanship in the electorate through a chart from the American National Election Studies (ANES), which shows that the number of strong partisans has spiked significantly over the course of the last decade. Many voters who would have considered crossing the partisan divide for the right candidate on the other side simply do not countenance such a thought any longer. Money is a tool by which to project messages convincing swaths of the electorate to vote for a candidate, but if the electorate is simply not receptive to hearing these messages in the first place, its impact would be blunted.

This is not to say that money does not matter. On the contrary, estimates done by Split Ticket and by other independent sources have found that financial spending still does move the needle noticeably; the point is simply that the movement is no longer nearly as significant as it might have been previously. In 2014, relative spending was nearly as predictive of the results as a state’s baseline partisanship; only four of 35 Senate elections in that cycle were won by the outspent party. But in 2020, 11 of 35 elections were won by the outspent party. And in all cases, it was the GOP that won despite spending less money.

This brings us to our next point: the growing partisan gap in money spent across candidates, parties, and independent interest groups. While Republicans outspent Democrats by $100M in 2014, Democrats took a commanding lead in campaign spending during the Trump era, spending $14.8 billion between 2016 and 2020, and significantly more than the $11.1 billion spent by Republicans over that time. One may argue that this asymmetry was driven by the fact that Democrats were the party out of power in 2018 and 2020. But it is not necessarily clear that this surge is actually attributable to that — in the Bush years, between 2002 and 2006, Democrats were actually outspent by Republicans, spending 49% of the non third-party money in elections over that period.

It may instead be the case that the reason for this growing spending gap has largely to do with factors related to the ongoing, educational polarization-fueled realignment. This relationship is clearly shown by the chart below, which plots the college-educated support rate for the Democratic Party to its percent of money spent for election cycles between 1998 and 2020 (save for 2006 and 2010, where partisanship splits were unavailable).

There is a very clear correlation between the amount of money spent by a party and its college educated vote share; the greater the share of college-educated voters that a party gets, the greater its share of spending in a cycle. As an example, from 1998 to 2014, the Republican Party was responsible for 51% of the (non-third party, inflation-adjusted) money spent in elections, and in 2014, they were getting 51% of the college-educated vote, as per Catalist. From 2016-2020, their spending percentage plummeted to 43%; perhaps not coincidentally, they were only netting 41% of the college-educated vote by 2020.

This correlation should come as little surprise, given the strong relationship between income and education levels. As the Democratic Party continues to pick up educated suburbanites, its coalition has proceeded to become wealthier than ever before, and it is reflected in the asymmetric spending spike the Democratic Party has seen of late. In fact, by 2020, Joe Biden and the Democratic Party received six times as much secret donor support (termed “dark money” by some) as Donald Trump and the GOP did.

And so while it was once taken as a given by many Democrats that the increase of money in politics might result in Republican hegemony at the ballot box, the picture is now no longer as clear; campaign finance reform measures might genuinely hurt the Democratic Party more than it would harm the Republican Party. But if 2020 was any indication, it might not ultimately matter as much any longer as to which party spends more money. With both parties sure to be awash in cash and with the importance of partisanship at an all-time high, the value of a dollar may never have been lower.

Sources:

The American National Election Studies Guide to Public Opinion and Electoral Behavior

Two Way Partisanship data from Catalist

Spending data from OpenSecrets