The Left and Right share one major goal: make the activist left the face of the Democratic Party.

This dynamic in the Texas Senate race is dominating headlines today, but it has been just one week since the special election in Tennessee.

Last week, I talked to Shane Goldmacher for a story in The New York Times about this paradox:

“It is healthy for the party to have a clear experiment of, ‘Can you get over the hump in a red district running a Brooklyn-style campaign?’” said Liam Kerr, a co-founder of Welcome PAC, a group that promotes centrist Democrats.

“She was the dream candidate — for both the online left and for Republicans, as so often happens,” Mr. Kerr said of Ms. Behn. “She is exactly who the online left wants to be the face of the Democratic Party and who Republicans wanted to be the face of the Democratic Party.”

The 13-point swing toward Democrats was actually the smallest of the five congressional special elections that were held this year outside a major election day.

Multiple Republican operatives said the party would have stronger chances in 2026 if Democrats — who are facing a large number of primaries — nominate more candidates that can be more easily caricatured.

“We need Democrats to continue to be crazy, to say crazy things and be for crazy things,” said Corry Bliss, a veteran Republican strategist who guided the party’s leading House super PAC during the 2018 midterm elections. “It helps to provide a contrast.”

Instead of persuading voters to support a candidate with moderate positions in a localized race, Democrats focused on juicing turnout for a leftist. But what excites Democratic primary voters also excites Republican ad buyers, who were quick to seize on comments Behn made about policing and support for radical policies. Behn was explicit that her campaign was focused on mobilizing “disenchanted” voters rather than persuading, and she invited Harris to campaign with her.

When Democrats lose, it’s normally best to avoid saying “The Democrats” because the party is a loose constellation of entities, not one coherent organization executing a strategic plan. But in this case, the literal Chair of the DNC said the focus was on turnout, formal party entities invested millions, there were rallies with AOC and Kamala Harris, and the candidate hit the sour spot of “willing to go on MSNBC but unwilling to answer their question about past support for defunding police.”

But this is not Aftyn Behn’s fault, or Kamala Harris’s fault, or even the fault of the formal Democratic Party entities who waded into the race.

Centrists just need to try harder to win tough races.

At some point it’s our fault

One nice thing about being a startup - and about being an outsider - is that you can critique the establishment with all your brilliant fresh ideas. Four years to the day before the TN-07 special election, WelcomePAC made its first media appearance with an interview in Slate titled How a Centrist Is Completely Rethinking How to Get Independents to Vote for Democrats.

Kanter’s Law posits “everything can look like a failure in the middle” of a new endeavor. After the excitement wears off, you enter the “messy middle” and must persevere with flexibility, adapting, and remaining focused on the long-term goal.

After a burst of energy from Bernie Sanders’ 2016 run through the 2020 presidential primary, the far-left peaked then descended. Justice Democrats started recycling candidates, Our Revolution floundered, and founders left for other startups which have mostly failed to break through.

Centrist political entrepreneurs need to avoid the same fate.

In the four years since we were “completely rethinking” how to win red districts, Welcome has grown to a team of nine and has invested more than $18,000,000 towards that mission. Excitingly, we are joined by a burst of partisan centrist entrepreneurship tackling similar problems, with new entrants like the heterodox think tank Searchlight and elected official collaboration Majority Democrats, and innovative incumbent investments like PPI’s stewardship of the grassroots Center for New Liberalism and Third Way’s Moderate Venture Fund.

Growth is exciting. It also comes with responsibility.

Why no centrist nominee in Tennessee?

Welcome conducted due diligence on the TN-07 race back in June, when GOP Rep. Mark Green’s resignation triggered a special election.

Secondary source data, like election results and demographics, made it clear there was potential volatility that could be harnessed for a shock upset. Favorable macro conditions made it possible, with Trump favorability and other special election results putting a Trump +22 district firmly in play. Three months earlier, Trump withdrew the UN nomination of Rep. Elise Stefanik due to concerns over losing a similar district.

Our investment thesis required us to consider what level of candidate differentiation would be required. And based on all case studies (and common sense!) we thought it was a lot. The last two special election surprises, Conor Lamb and Mary Peltola, both took conservative positions on guns and energy production. You have to go back to 2008 to find similar upsets, with winners in Louisiana and Mississippi touting conservative positions on guns, abortion, and illegal immigration.

A “moderate Democrat” wouldn’t be enough. We’d need a conservative Democrat, or at least a Democrat who held enough conservative positions to reflect the opinions of voters.

Which brought us to our primary research. We engaged partners to get an on-the-ground understanding of the potential candidates. Our due diligence process in the potential special election in Stefanik’s district yielded a candidate we thought could win and hold the seat.

But not so in Tennessee. After much internal deliberation, we could not justify the significant investment it would take to impact the primary enough to make the race winnable.

That may have been the wrong call.

A Muscle, Not a Battery

One of our favorite lines is from Elizabeth Warren. At a 2017 college event, she was asked about the political infeasibility of proposed battles like student debt cancellation. Warren replied:

“Getting into these fights is not like draining a battery. It’s like a muscle. The more you use it, the stronger it gets.”

Over the past decade, progressive entrepreneurs spotted upside in everything, building a community through line from campaign to campaign.

There are no total losses when every conflict yields assets that carry over into the next round. Leftists leveraged their fights to build power and connective tissue, jumping into issues with an energy that drove progressive narratives and built community.

Centrists have typically approached fights the way WelcomePAC’s due diligence process did: a rational exercise in understanding the opportunity cost of a certain investment. More like strategically nursing an iPhone battery at 8% than building muscles.

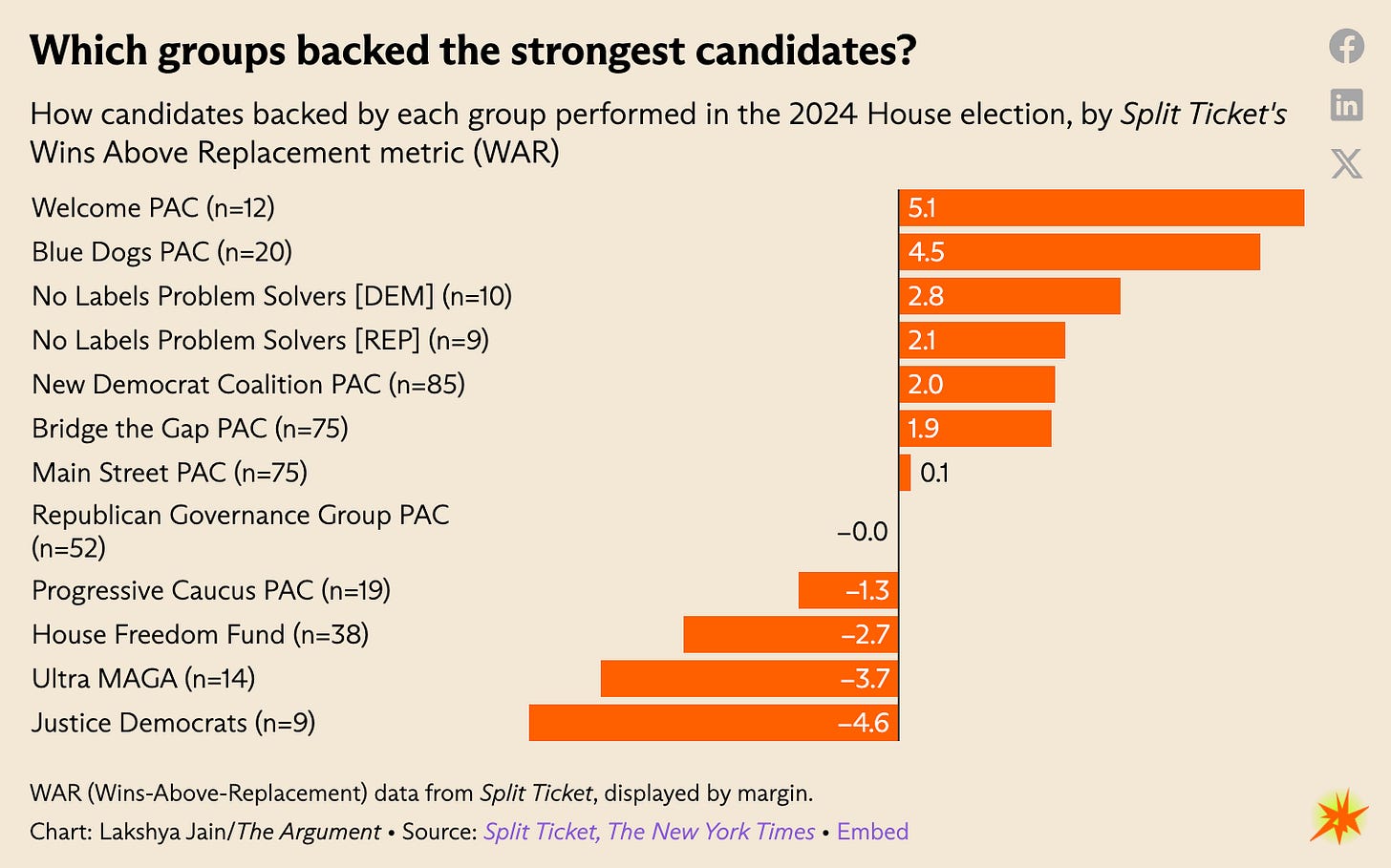

This venture approach to electoral politics has identified overperformers at a higher clip than any other major Democratic (or Republican) entity over the past four years (as The Argument’s Lakshya Jain showed).

But we don’t need better bar charts. For a commonsense Democratic Party to win consistently, the centrist community needs to try harder to win races in a way that builds muscle.

Missing Muscle

While we give progressive entrepreneurs a ton of credit for moving the party so far left, there is a hidden reason driving the dearth of centrist power: the would-be leaders lost their races in 2010 and 2014. Why don’t Democrats contest right-leaning voters, districts, and states more aggressively?

Stefan Smith has a compelling thesis that we have a “missing generation of campaign operative and political staffers who should be in powerful positions in the party right now but their members were defeated in wave elections in 2010 and 2014. If it feels like the people in charge aren’t up for this moment, it’s because they’re largely the staff of safe district Democrats who survived that moment. And that has some benefits, but it’s also a filter for a certain type of politics.”

In 2010 alone, Democrats lost 6 governorships, 6 Senate seats, 63 House seats, and more than 680 state legislative seats. That is thousands of elected officials, chiefs of staff, communications directors, policy directors, legislative aides, and field organizers.

And it is not a random sampling of talent: these staffers were, by definition, engaging the realities of swing districts at every level.

Red waves in 2010 and 2014 didn’t just cost seats, it decimated the ecosystem of operatives and junior staff who should, by now, be in senior strategic positions. Survivor bias is rampant: operatives who did succeed in that era were “disproportionately clustered in safe districts, and built their political instincts in low-risk environments. That’s who got promoted. So now, the dominant strategic class was filtered by structural insulation … the problem isn’t just who’s missing, it’s what mindsets, urgencies, and adaptive instincts were never formed.”

Now we need to do the opposite.

In the debates following the Tennessee special election, the founder of Run For Something said the “reply guys” arguing Democrats need to get in the game: “Got a theory of the case? Recruit the candidates & prove it or shut the fuck up.”

She’s right. In a very real way, it doesn’t matter that centrists have the facts. Organizing beats debating. Centrists need to try harder to win tough races1, even if it is tougher in the middle. It is the best way to build muscle, and we’ll need some big muscles to win.

Stay tuned for endorsements soon :)