Episode 1: How We Got Here

Theme: From 1950’s to today, parties sort along ideology

Guests: Matt Yglesias & Sam Rosenfeld

It’s a complaint we hear endlessly about American politics: why is everything so polarized? Our new podcast series, The Depolarizers, discusses how we got here and more importantly, how we get out of it. Our recent essay in Democracy Journal introduces a number of the themes in our podcast. We recommend including it in your podcast journey.

Our first episode features Matt Yglesias, writer of popular Substack publication Slow Boring, and Sam Rosenfeld, author of two books about polarization (The Polarizers and his latest with Daniel Schlozman, The Hollow Parties). Rosenfeld’s book inspires the name of our podcast. In it, he introduces us to those who created America's polarization in the 20th Century, and why. Throughout this episode and our show, we’ll introduce you to the people working to effectively depolarize American politics. We hope you'll join us for the ride.

To know how to move forward, we must first understand how we got here. What is the origin of strong partisanship and weak parties? As political scientist Sam Rosenfield explains in The Polarizers, the source of our current polarization is the product of an intentional strategy – not from radical extremists, but from well-intentioned, sympathetic activists in postwar America. These activists wanted the parties to be rooted not in regionalism and patronage, but rather ideological principles that voters could understand. Franklin Delano Roosevelt once said to an aide, “We ought to have two real parties – one liberal, and the other conservative.”

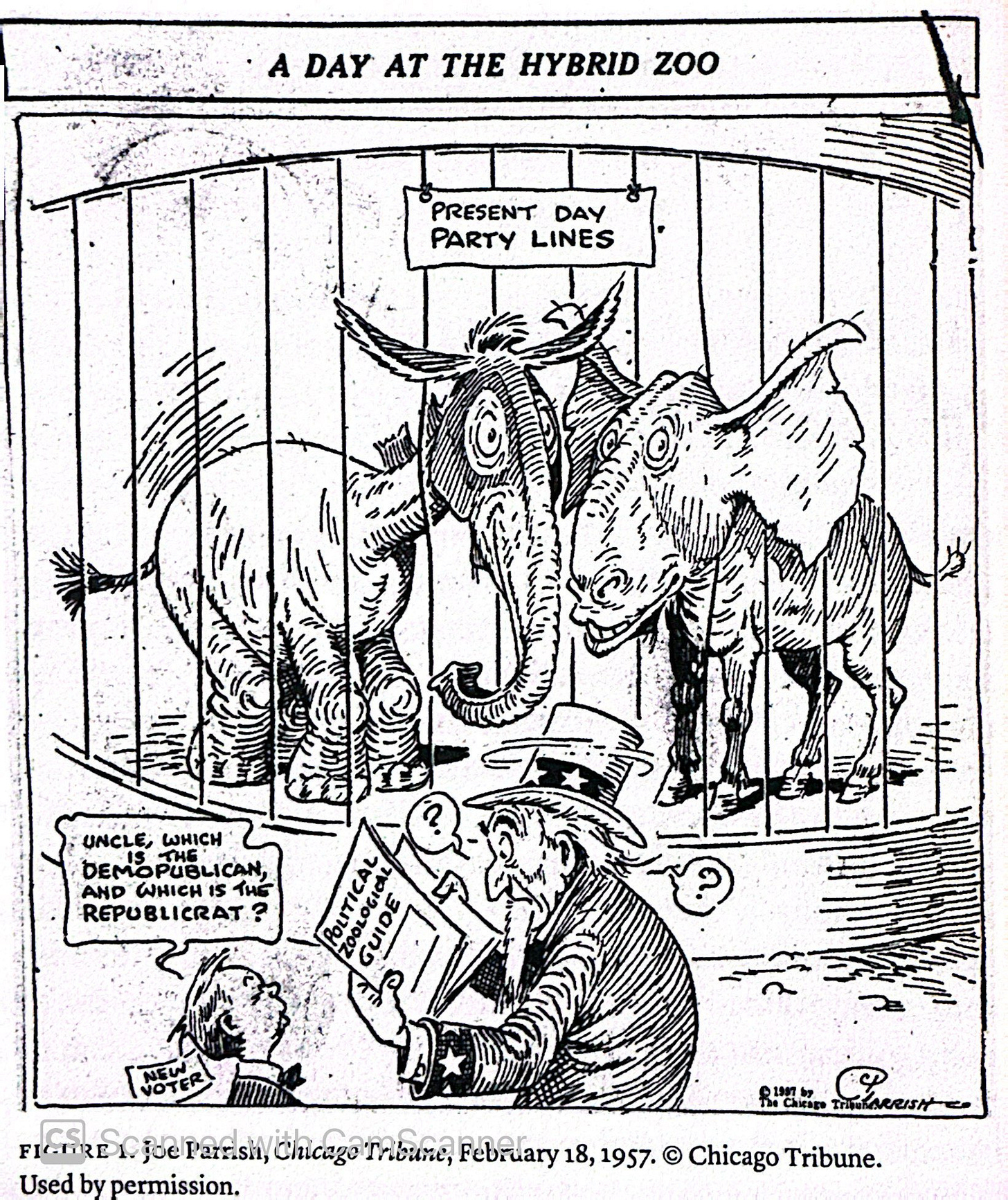

At the time, the parties were not ideologically sorted; Northeastern Republicans were more liberal on economic and racial issues than Southern Democrats. But many, including leading advocates, political scientists and politicians, believed that it would be good for the parties to be sorted by ideology. This view was enshrined in The Responsible Two-Party System, a tract written by political scientists including E.E. Schattschneider that argued for ideologically coherent parties.

These activists and political scientists argued that the lack of ideologically coherent parties constituted a failure of democracy – voters might give Democrats a national majority, but this would only empower Southern Democrats who had meaningfully different preferences. At the time, it was a live debate: Gallup frequently polled voters on the issue and found consistent voter rejection of the idea of ideologically consistent parties. When Gallup polled the question of a liberal party and a conservative party in 1947, only 13 percent of voters endorsed the idea.

Over time, activists on both the left and right successfully shaped the parties into ideologically coherent structures. Southern Democrats slowly became Republicans, and the newly redrawn GOP coalesced around conservative ideology. The Democratic Party also became more ideologically coherent, though their more diverse coalition caused a big tent to remain slightly less ideologically homogeneous, as political scientists Matt Grossmann and Daniel Hopkins have argued (and any attendee of a Democratic National Convention can attest). Ideological liberals have long represented a smaller share of the electorate than conservatives, making a viable liberal-dominated party impossible, and the Democratic Party includes a wide range of African American moderates and conservatives that prevented ideological homogenization.

As the parties became more ideologically coherent, the merchants of policy purity gained power. Unlike past factional leaders, they did not wield power through government patronage, but rather through ideas and increasingly through outside groups like nonprofits and PACs. These leaders and their organization shaped the ideological battlefield. They did not organize voters through material demands, but ideas. Groups like the Moral Majority and the religious right, the environmental movement, the National Rifle Association and many others sought to define the parties’ respective missions.

This unmooring from the demands of the traditional party bosses came with an unintended downside: Those wielding power within the parties have less interest in winning long-term electoral power. For autonomous, often issues-focused groups, winning elections can be tangential to the lifeblood of nonprofits: donors and volunteers. In fact, groups often find themselves in the most fecund fundraising environment when their party is out of power. This trend cuts across branches of government; witness the explosion among Democratic activists and donors since the Dobbs decision.

For factions on the edges of each party, the goal is not exclusively to ensure the party wins, but rather ensure that the factional agenda is passed when the party eventually does win – or at least that their patrons of time and treasure believe that to be so.

The factional actors dismissing electoral success is logical: once a party gains power, the dominant faction can determine the agenda. Thus, groups like the Sunrise Movement prioritize their clout within the Democratic Party, even if their litmus tests might – and do – cost Democrats elections. Similarly, the pro-life movement prioritizes beating moderate Republicans, even if these members are necessary for Republicans to have power.

Consider the quote from one organizer within the Democratic Party, “A smaller but more progressive Democratic Caucus would be a more functional and healthy and coherent caucus.” This view has been echoed by conservative activists, who also do not prioritize the electoral fortunes of their aligned party.

We are in the age of faction, and centrists must learn from the tactics of the factionalists on both the left and right. However, centrists bear one burden that extremists do not: an inability to sacrifice the electoral interests of the party winning. The good news is that a pragmatic agenda is much more aligned with political victory. To beat the extremists, centrists must understand how they are structured.

Like what you’re hearing? Listen to the full episode on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you find your podcasts, and subscribe to hear new episodes of The Depolarizers every Monday.

You can also support our work to depolarize American politics via our 501(c)3, The Welcome Democracy Institute.

SHOW NOTES:

Polarization is a Choice - Matt Yglesias via Slow Boring

Political cartoon mentioned in show in Rosenfeld’s book, The Polarizers