The emerging Republican majority?

The pandemic pushed young voters to the right — and without a change in message from Democrats, they’ll stay there

The first time Donald Trump was inaugurated as president, I watched his speech on the 8th-grade history classroom projector (our teacher thought it important that we witness the peaceful transition of power, a hallmark of American democracy). This time, I watched the speech on my laptop while I cleaned up my dorm room.

Since Trump won the 2024 election, there have been countless articles written about how he did it. How did Republicans manage to win over millions of people who voted for Biden four years ago? Was it those “Kamala is for they/them ads”? And how much, exactly, did Trump gain with nonwhite voters?

One consistent theme in the postmortems has been the rightward shift of young voters, usually defined as those between the ages of 18 and 30. At a recent rally in Washington, DC, Trump himself claimed that he won the youth vote by 36 points.

I voted for Harris. But I understand why, after the last four years, a lot of people around my age voted for Trump.

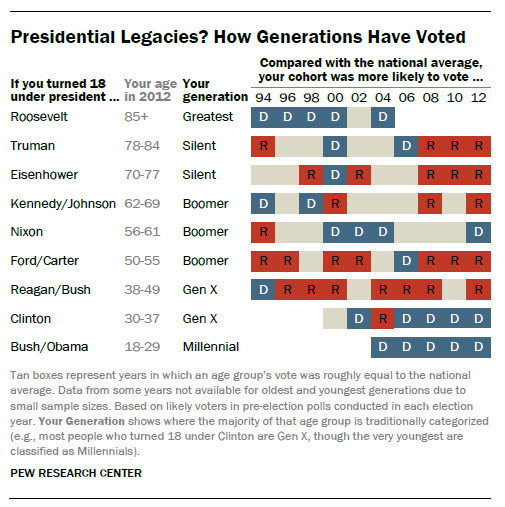

It’s often treated as gospel that young people lean left while older people lean right. “To be conservative at 25 means you have no heart,” the saying goes. “But to be liberal at 45 means you have no brain.” However, in America, age polarization is a relatively recent phenomenon. In 2000, senior citizens voted to the left of young people. In the 1960s and 1970s, younger voters were consistently more Republican than older voters.

Age polarization peaked in 2008, according to figures from Split Ticket.

People who were 18 to 30 around 2008 — Millennials — have remained a fairly blue cohort, at least according to surveys by Pew Research.

Why is that? I believe that this relates to a person’s “formative political experience” — the most significant events around the time you start engaging with politics. For Millenials, that includes the Great Recession and the Iraq War, both of which were widely blamed on the Republican Party.

My theory is that your formative political experience tends to shape the way you see politics and that once those fundamental views are set, they are hard to dislodge. There is evidence that people who lived through the Great Depression voted differently for the rest of their lives (based on economic issues rather than social issues) than those who did not.

That is the key to understanding why young people have shifted to the right. Today’s young people aren’t the same group as the young people of 2008. I was 5 years old when Barack Obama was elected president. I was 8 years old when the Iraq War ended. For my generation, the formative political experience was the COVID-19 pandemic. Everyone I know can say exactly where they were when they first heard about their school closing; I was sitting in 11th-grade English class.

And to many, the pandemic has become associated with an overreach by left-leaning institutions and actors, in the same way that the financial crisis and Iraq were seen as the consequences of right-wing overreach by Millennials.

COVID-19 led Democrats to embrace policies that alienated young people. Mask mandates persisted even after vaccines became widely available, or were themselves mandated. Schools were kept closed even though restaurants and bars were allowed to reopen, while blue state governors violated their own lockdown orders. Standardized tests were scrapped in favor of diversity programs which often discriminate against Asian-American students. (It is not a coincidence that Asian-American voters in Virginia swung 24 points right.)

One recent paper from the London School of Economics looked at historical polling data from 2006-2018. It found that “individuals who experience epidemics in their impressionable years (ages 18 to 25) display less confidence in political leaders, governments, and elections.” The study found that greater exposure to an epidemic reduced confidence in the honesty of elections, reduced confidence in the national government, and reduced job approval of incumbent political leaders, with these effects being “larger in middle- and high-income countries than developing ones.”

There are growing signs of a broad-based loss of trust in the system. Consider the way that raw milk has become a signal of cultural conservatism. Or the fact that childhood vaccination rates against measles, polio, and whooping cough have been falling since 2020. Since 2020, average confidence in major US institutions has fallen from 36% to 28%, according to Gallup.

In interviews, Elizabeth Warren has sometimes told the following story about her grandmother and FDR:

“My grandmother had never been very political, and she sure didn't follow high finance. But decades later, she was still repeating her line that she knew two things about Franklin Roosevelt: He made it safe to put money in banks and---she always paused here and smiled---he did a lot of other good things.”

This rightward shift in young people’s politics is more likely than not to persist without a dramatic shift in approach from the Democratic Party. Once your political views are formed — by a depression, a financial crisis, or a pandemic — they calcify. The LSE paper cited above noted that the effects they found “represent the average treatment values for the remainder of life - they decay only gradually and persist for at least two decades.”

This makes it all the more vital for Democrats to reject the failures of the far-left and embrace a common-sense approach to politics, focused on meeting people where they are.

Whether a widely-held belief system “accords with justice and sound judgment, is not the sole question, if indeed, it is any part of it,” said Abraham Lincoln. “A universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, can not be safely disregarded.”1 That quote is from a portion of a speech against the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which lifted the prohibition on slavery north of the 36° 30′ line. Lincoln was a lifelong opponent of slavery;2 he saw it as a moral wrong that denigrated the principles laid out in the Declaration of Independence.3

However, Lincoln understood that it would do the antislavery cause no favors to take a maximalist stance that cost them the election. “Public opinion in this country,” he said, “is everything.”4 Lincoln clinched the Republican nomination in 1860 as the common-sense alternative to William H. Seward and won the general election as a relative moderate on slavery. As president, he was often criticized by abolitionists for not moving quickly enough against slavery.

No challenge we face today is greater than that faced by the Emancipator. But if Lincoln could see the need for compromise and moderation to eliminate the scourge of human bondage, then how can it be that compromise is unacceptable today?

The new parents who aren’t sure whether they’ll be able to pay for childcare for their toddler; the woman who’s afraid to start a family because of state laws that put the government in her doctor’s office; the young man, working his first job and unsure whether he’ll ever be able to afford a place of his own — will another round of corporate welfare for Trump and Elon’s billionaire golf buddies make their lives easier? Those are the stakes — today, next year, and in 2028.

As Democrats chart our path out of the wilderness, I suggest that we adopt a modified version of the closing line of Lincoln’s second inaugural address as our watchword:

With malice towards none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the party’s wounds, to heed those among us who win tough districts, and to do all which may aid us in beating JD Vance in 2028.

Speech on the Kansas-Nebraska Act at Peoria, Illinois (October 16, 1854).

Letter to Albert G. Hodges (April 4, 1864).

Letter to Joshua F. Speed (August 24, 1855).

Speech in Columbus, Ohio (September 16, 1859).

The Democrats still won a margin among 18-29 year old voters of +13, despite Trump's imaginary world, though down quite a bit from the margin of +24 in 2020. That 11 point decline in the Dem margin (really a 5.5 shift since a 1% shift from D to R results in a 2% change in margin) compares to the total vote margin shift of about 6% but it doesn't compare with the largest shift that really decided the election which was among Hispanics where the margin shifted a full 25%. A good chunk, and I leave it to somebody else to do the math, in 18-29 year olds might be a reflection of the Latino shift. Latinos are 15% of eligible voters but being a younger population a bigger proportion of young voters.

Data Source https://www.nbcwashington.com/decision-2024/2024-voter-turnout-election-demographics-trump-harris/3762138/