The House Retirement Crisis

This cycle, a historic number of lawmakers are rushing to the exits. It's a warning sign about the health of the institution.

Washington has always been dysfunctional. But this Congress is something else entirely.

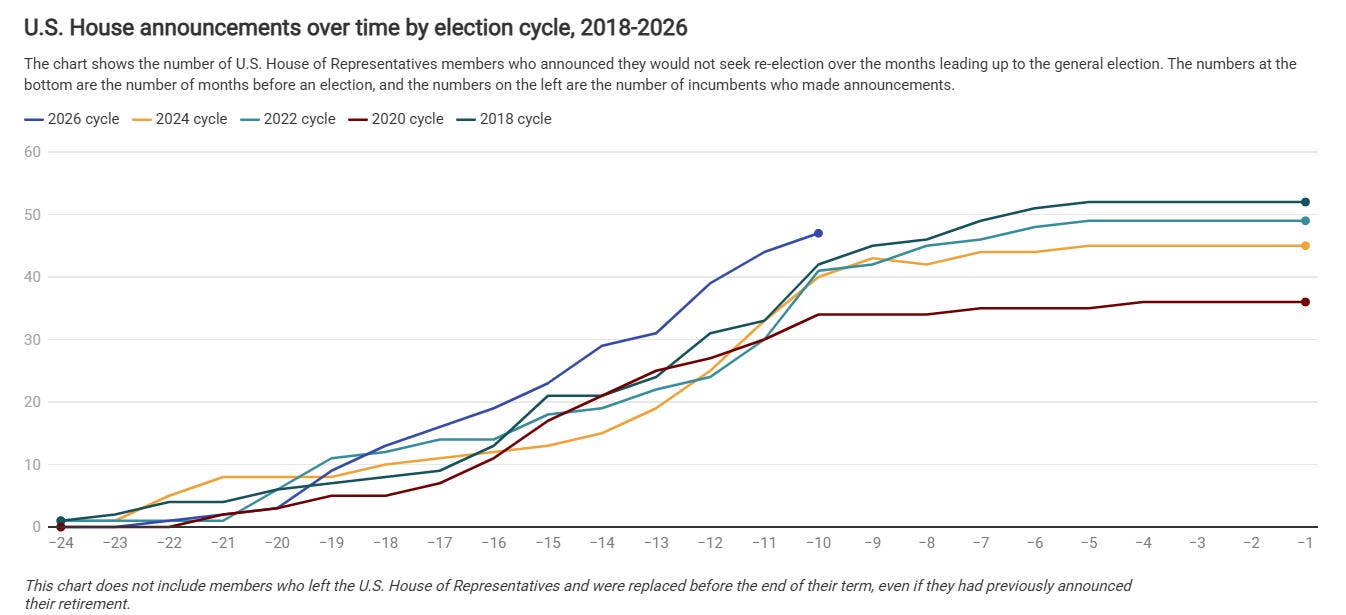

As we enter 2026, we are on track to see a record number of retirements from the U.S. House. Many of these retirements are driven by age and opportunity, but an increasing share are driven out by the growing consensus among lawmakers that serving in Congress has become an exercise in futility.

Retirements Outpace Past Cycles

As of today, 47 members of the U.S. House have announced their retirement from Congress. This does not include the four members who have died in office or the four members who resigned from office early during their terms.

The majority of House retirements are on the Republican side, accounting for 26 while Democrats account for 21 retirements. Roughly 44% of retiring members are retiring from public office altogether, while the remaining members are retiring to run for other political offices (14 are running for Senate, 11 are running for governor, and Chip Roy is running for state attorney general).

Congressional Dysfunction Is Driving Retirements

The House has become increasingly unproductive in recent sessions, but the 119th Congress has been spectacularly dysfunctional. Members spent months talking about the One Big Beautiful Bill, narrowly passed it, and then almost immediately pivoted to a government shutdown. Even when Congress manages to legislate, it feels temporary, with shutdown threats, discharge petitions, leadership fights, and razor thin margins becoming the norm.

For Republicans especially, the incentives to stick around are even worse. With the House likely to flip or become even more narrowly divided, many GOP members are staring down a future defined by minority status, endless messaging votes, and no meaningful ability to govern (not that they are really able to govern now). For lawmakers who want to accomplish anything, the House increasingly looks like a dead end.

What makes this wave of departures especially alarming is that it’s not limited to aging members at the end of long careers. We’re also seeing mid-career lawmakers, many of them electorally successful, deciding the House simply isn’t worth it anymore due to growing partisan extremism. In Maine, Jared Golden, a Democrat who repeatedly won in a Trump-leaning district, is walking away in his early 40s rather than endure another cycle of dysfunction. The fact that he is already forced to run a competitive general election every two years and must now also run a competitive primary likely weighed on him.

Republicans like Morgan Luttrell and Don Bacon, who are neither fringe figures, both capable of winning again, have also chosen to exit rather than stay trapped in a chamber defined by paralysis and internal warfare. Even rising GOP leadership stars aren’t sticking around: Elise Stefanik is opting out of electoral politics rather than pivoting back to the House after her failed gubernatorial run.

When lawmakers who can win, do win, and aren’t anywhere near retirement age decide the institution isn’t salvageable, it’s a sign the problem isn’t electoral, it’s institutional. In fact, the House has become so dysfunctional that even Marjorie Taylor Greene left (and, alarmingly, sort of making sense while doing it).

As Experienced Members Retire, A Vicious Cycle Begins

That’s not a punchline. It’s a warning sign. When an institution deteriorates to the point that even its most chaos-embracing members decide it’s no longer worth their time, the problem isn’t ideological. It’s structural.

What makes this moment more concerning is that the dysfunction is no longer contained to the House.

For most of modern political history, the Senate has been viewed as the steadier chamber. Yet now, this same dynamic is bleeding upward. A growing number of Senators are choosing not to seek reelection, and several are opting to leave mid-career to run for governor, a historically rare move.

As of today, 9 Senators have announced their retirement, well ahead of the pace from the last four cycles. In fact, the last time there were more than 9 retirements in the Senate was during the 2010 cycle, when 11 Senators decided to retire. Eight of them are retiring from public office altogether, however, Tommy Tuberville is retiring to run for Governor of Alabama.

Tuberville is not the only Senator who is looking to ditch the commute to DC and work from their home state. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) and Michael Bennet (D-CO) are also running for governor (although not retiring to do so, meaning they can stay in the Senate if they lose their gubernatorial race). Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) is “seriously considering” a run for Governor in Minnesota.

That makes 4 sitting U.S. Senators who are actively looking to leave this distinguished body to become the top executive in their home states. According to long-term Ballotpedia data, relatively few sitting Senators have run for governor since direct election began in the early 20th century. Since 1912, just 23 sitting Senators have run for Governor, and less than half of them ended up winning. The fact that we’re seeing multiple sitting Senators make that choice now underscores how unusual and unsettling this moment is.

The result is a vicious cycle: experienced members leave, institutional knowledge erodes, volatility increases, and Congress becomes even less functional, which in turn drives more exits.

Judging by the current trajectory, we shouldn’t expect this exodus to slow anytime soon. In fact, all signs point to more retirements ahead, not fewer.

That’s the backdrop for the 2026 cycle, and the institutional reality shaping everything that follows.

Chart Source: Ballotpedia

What if, now hear me out, turnover is good? (and you should have stats on the number of announced House retirements at this point prior to midterms in each of the past couple decades).