Win the Middle Part 2: (Far) Left Out

The influence of the far-left has hurt Democrats’ ability to win a sustainable majority. Here’s how.

Let’s be clear: this is where things get a bit controversial.

That’s why it’s important to establish something before we go any further: if you felt the Bern in 2016, donated to AOC in 2018, and bought a “She Has a Plan for That” bumper sticker in 2020, this is a safe space for you (though you might disagree with a lot of what we’re about to say). One of the core tenets of a Big Tent Democratic Party is that there is room for all of us. The problem is not that the far left exists as a faction within the Democratic Party. The problem is that the far left has subsumed the Democratic Party of today, dominating its fundraising ecosystem, issue spaces, and political dialogue — and jeopardizing the party’s standing with middle-of-the-road swing voters who we need to win to hold our majority.

We believe productive conflict with the far-left is necessary for moderates to be able to differentiate themselves from aspects of the party’s brand that are a liability in swing races and, in doing so, forge a faction of the party that is capable of winning everywhere. Intra-party conflict has never been simple, then or now, and it should be done with a sober evaluation of today’s reality, the stakes and the various structures such conflict can take.

This doesn’t mean fighting for fun, it means drawing important distinctions between factions in the Democratic Party to allow both to communicate more clearly to the rest of the country. Of course, conflict has real costs and can distract (and many on the far-left share motivations and goals with the center-left!), so questions are warranted.

Is conflict necessary? Is it truthful? Is it helpful?

The truth is that today’s far-left activist faction has made a big business out of rejecting political reality. In some cases, that’s fine — they can be left to advocate for pie-in-the-sky hashtags and are free to ignore swing districts without drawing unnecessary conflict. But as the old saying goes, your liberty to swing your fist ends just where my nose begins. Once the far-left threatens the party’s ability to sustain a durable governing majority (and begins costing the party swing seats), intervention is warranted.

So, with the goal of productive conflict in mind, let’s establish a few facts about the far-left’s influence on Democratic politics — and debunk a few myths while we’re at it.

1. Who is the “far-left”?

The “far-left” is our shorthand for the Democratic Party’s leftmost flank — specifically the small-but-vocal cohort of ultra-progressive Democrats aligned most closely with Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

When we talk about the far-left in electoral terms, we are referring not to “progressives” or even “the left” but rather the cohort of disruptive, ideologically-polarized candidates associated with and endorsed by the organizations Justice Democrats (which recruited AOC and “The Squad”) and Our Revolution (founded to carry on the mission of Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign).

Learn More:

Biden, Democrats and the marginalized can't afford to take the risks progressives can by Liam Kerr (NBC THINK)

Can Justice Democrats Pull Off a Progressive Coup in Congress? by Tessa Stuart (Rolling Stone)

What Didn’t Happen After Jan. 6th by Liam Kerr (The Bulwark)

2. The far-left has never flipped a single Republican-held seat. Ever.

The far-left has had a remarkable six-year run — at least on the surface.

In 2016, Bernie's momentum upended the presidential primary and spurred talk of political revolution.

In 2018, AOC led the four-member “Squad,” channeling the energy of Trump blowback and making talk of political revolution tangible.

In 2020, the Democratic presidential primaries were dominated by ideological litmus tests that would have been unthinkable in the Obama era, while the Squad grew from four to seven.

In 2022, the Squad grew by two more seats, from seven to nine.

Look a little closer, though, and things start to look a bit more complicated.

In 2018, the media narrative was dominated by coverage of the ascendant left. But the Democratic House majority was delivered by mainstream moderates. In the 2018 cycle, 33 moderate candidates flipped red House seats to blue, while not a single Our Revolution-endorsed candidate captured a red seat. Moderate Democrats won 6 of 10 general elections for governor in the Midwest and other presidential battleground states — including governorships in the “Blue Wall” states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. These governors played a critical role in saving our democracy in 2020 and protecting a woman’s right to choose in 2022.

In the runup to 2020, the Democratic presidential primary debates were indeed dominated by debates over Medicare for All, the Green New Deal and other items on the progressive wish list. But it was Joe Biden — a moderate promising a return to normalcy — who ultimately prevailed in a grueling primary contest. Justice Democrats went from endorsing 69 House candidates in 2018 to just eight in 2020, all of whom ran in districts with an average Democratic advantage of 20 points. Of the three Justice Democrats who won that year — Cori Bush, Jamaal Bowman, and Marie Newman — two were second-time candidates (Bush and Newman) who had run unsuccessfully the cycle prior.

In 2020, moderate Rep. Abigail Spanberger, who won her seat as part of 2018’s Blue Wave, didn’t mince words after she nearly lost her race in Virginia’s 7th district. According to Spanberger, the unexpected closeness of her race (she narrowly won 50.82% to 49.0%) was due to the fact that the far-left brand had become a toxic liability among voters in her district.

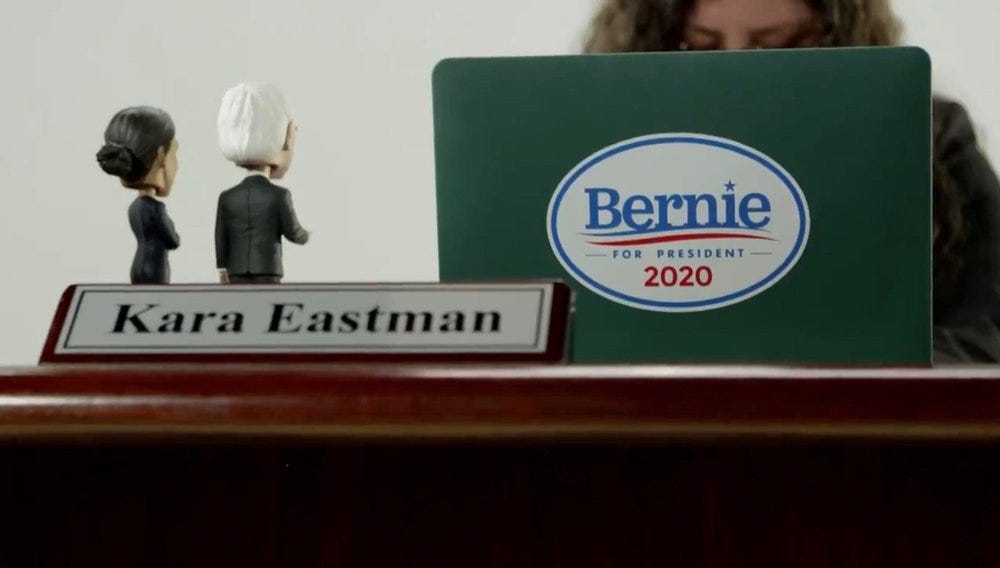

2020 was also the year that the far-left lost a swing seat that Joe Biden won handily at the top of the ticket. When a far-left nonprofit executive named Kara Eastman ran for Congress in Nebraska’s 2nd district, she underperformed Joe Biden by double digits.

Case Study: The Other Eastman Memo

Finally, in 2022 the far-left successfully primaried a moderate Democratic incumbent in a newly-drawn Oregon district (OR-05) where Joe Biden won by a nine-point margin in 2020 — only to lose that seat to a Republican challenger by two points. The Squad added two seats, but as in the case of Kara Eastman in 2020, the far-left underperformed Joe Biden by double digits in a seat Democrats should not have lost.

Justice Democrats and Our Revolution looked like unicorns when they first appeared on the scene in 2018, but, as Third Way points out, Justice Democrats and Our Revolution have never flipped a single seat from red to blue in the three cycles of their existence. After the debacle in OR-05 last cycle, the far-left has now officially flipped more seats from blue to red than the other way around.

But that’s not all. The far-left’s growth in blue seats is slowing too: the Squad only has nine members now, almost half of whom were elected in 2018.

There is much to admire in (and learn from) the early successes of the far-left political entrepreneurs who launched Justice Democrats and Our Revolution. They did a lot with a little right off the bat and achieved an outsized impact.

But times have changed since 2015 — and so have the stakes. Leading up to 2024, it is up to the center to save democracy and ensure a Democratic majority. It’s time for the center-left to have its own five year run.

Learn More:

Comparing the Performance of Mainstream v. Far-Left Democrats in the House by Lanae Erickson, Lucas Holtz, and Maya Jones (Third Way)

The 2018 Midterms: A Blueprint for Democrats in 2020 (Third Way)

The Other Eastman Memo (The Welcome Party)

Oregon Fail (The Welcome Party)

Has the Far-Left Peaked? (The Welcome Party)

Progressive Groups Are Getting More Selective In Targeting Incumbents. Is It Working? by Nathaniel Rakich and Meredith Conroy (FiveThirtyEight)

What the Center Can Learn From AOC (The Welcome Party)

3. The far-left relies on turnout myths to avoid having to persuade swing voters.

For as long as there have been Democrats, there has been the theory that progressive policies will drive massive turnout among less likely voters (most commonly young people and people of color) — and that, therefore, candidates should spend their time trying to “fire up the base” rather than persuade those on the fence between the two parties.

This idea has been the animating principle of Bernie Sanders’ two runs for President and that of his many acolytes up and down the ballot in the years since.

It’s a wonderful idea, in theory. The problem is that it’s wrong. While base turnout certainly matters in elections, persuasion of swing voters is just as important.

According to a summary of research done by the team at Split Ticket:

“Prior studies show that ideological extremism, in general, tends to actually hurt turnout rather than helping it. A 2018 study by Andrew Hall and Daniel Thompson found that ideologically extreme candidates tend to give the opposite party a higher turnout boost than anything and actually get lower relative turnout than more moderate candidates. This is backed by a 2014 study by Jon Rogowski, which finds that increased levels of ideological conflict actually drove down turnout. All of this serves to counter the notion that attuning one’s stances to primary electorates helps margins in the general election through firing up base voters.”

Ruy Teixeira, Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and co-founder of The Liberal Patriot, calls the turnout myth “a sort of pixie dust that you sprinkle over your strenuously progressive positions to ward off any suggestion that they might turn off voters.”

This pixie dust allows some Democrats to ignore the fact that in 2018, when Democrats took back the House and netted 40 seats, nearly all of the gains were due to persuading voters who went for Trump in 2016 to back Democrats in 2018 — not some mythical surge in turnout.

Unfortunately, persuasion in the opposite direction is why Democrats lost the 2021 gubernatorial race in Virginia and nearly did the same in New Jersey, despite the fact that Joe Biden won both states handily just a year beforehand. Here’s what the Democratic data firm Civis Analytics had to say in their post-mortem of these upset races:

Vote switching accounts for about 80% of the shifts in each state from Biden in 2020 to the Democratic candidates for governor in 2021. Changes in turnout only account for about two-tenths of overall movement. In terms of the final margin, a switched vote is worth twice as much to the recipient because one side loses a vote while the other side gains one.

Things generally swung back in the 2022 midterms, in which persuasion of moderate Republicans and independents is what allowed Democrats to hold the Senate. As Nate Cohn writes for the New York Times:

“High-profile Republicans like Herschel Walker in Georgia or Blake Masters in Arizona lost because Republican-leaning voters decided to cast ballots for Democrats, even as they voted for Republican candidates for U.S. House or other down-ballot races in their states.”

The far-left likes to counteract sober concerns about real swings among independents and voters in the middle with the argument that across-the-board increases in turnout inherently benefit Democrats. But that belief is a fallacy: studies have shown that bipartisan increases in turnout mean increased volatility in who turns out for each party. As turnout expands, less-ideological voters with weaker partisan commitments account for a greater share of the votes — and these voters are by no means guaranteed to break for progressives.

At the end of the day, the great danger of the turnout myth is that it is often used to absolve Democrats from talking to moderate, persuadable voters who are also reliable voters, which election after election has shown we cannot afford to do.

Engaging less-likely voters is crucial to our democracy, and this is not an argument to ignore them. But assuming that progressive policy alone is going to drive up turnout on the left — with no repercussions or response and by a significant enough margin to win by — verges on magical thinking.

Learn More:

Turnout Myths Are the Democrats' Drug of Choice by Ruy Teixeira (The Liberal Patriot)

No, radical policies won’t drive election-winning turnout by Ruy Teixeira (The Washington Post)

2021 VA/NJ Vote History Analysis by Josh Yazman and Anna Mather (Civis Analytics)

Turnout by Republicans Was Great. It’s Just That Many of Them Didn’t Vote for Republicans. By Nate Cohn (The New York Times)

4. While the far-left underperforms, moderates overperform — and even win right-of-center districts.

There’s a common maxim in Democratic politics to “meet voters where they are”. In recent years, this sentiment has conjured up images of Beto O’Rourke visiting all of Texas’s 254 counties in a minivan.

But meeting voters where they are geographically is just one part of the equation. The other (we would argue more important) part is meeting them where they are ideologically. As WelcomePAC co-founder Lauren Harper points out in The Bulwark: “the hard facts of the case are clear: In general, moderates who can distance themselves from the Democratic party’s far-left national brand tend to do better in swing states than progressives who run toward it.”

Unlike the turnout myth, this claim is actually supported by research. According to an analysis by FiveThirtyEight’s Nathaniel Rakich (who looked at the House districts where Democrats outperformed President Biden’s margin of victory in their district in 2020): “The strongest candidates tended to be incumbents with moderate voting records and personal brands that differentiate them from the national reputation of their party.”

Also from Split Ticket:

“Research suggests that the path of electoral moderation is generally more influential, and comparing ideology against electoral performance shows that there is a significant and quantifiable penalty for ideological extremism. Political Scientist Dr. Chris Warshaw found that the penalty for ideological extremism generally ranges between 1.1 and 2.3 points in vote share for House incumbents; while the penalty for this has declined over time, it remains sizable, especially in close races (and especially considering that 39 seats were within 5 points of the national environment, on margin).”

The Split Ticket team has also noted that the members of the far-left Squad and the far-right “Dark Squad” (Boebert, Gaetz, Greene, etc.) were among the biggest underperformers of the 2022 midterm cycle. Meanwhile, the swing seat overperformers of the cycle were moderate, mainstream candidates who differentiated from the Democratic Party’s brand and appealed to independent and center-right voters.

As WelcomePAC co-founder Liam Kerr also wrote in The Bulwark, there was a red wave in the 2022 midterms — and it was bigger than expected. But the wave broke suddenly (a “dumper” in surf speak) when it reached brand-differentiated moderate Democrats in the swing districts that decide control of Congress.

For example look at Adam Frisch, who was the highest overperformer of the cycle in any seat where the Democrat won more than 35% of the vote and came within 546 votes of beating Lauren Boebert in Colorado’s 3rd district.

As a former independent who only registered as a Democrat before filing to run against Boeert, Frisch not only met CO-03 voters where they were physically, but ideologically. His campaign centered around building a “tri-partisan coalition” of Democrats, independents, and moderate Republicans. His website described him as a “patriotic mainstream businessman” with “the experience to work with both parties” on kitchen table issues like inflation, jobs, and public safety and highlighted his endorsement by Boebert’s moderate Republican primary challenger, Don Coram. Oh, and he also touted a robustly-branded “Republicans for Frisch” operation and ran advertisements designed to appeal to conservative and middle-of-the-road voters.

Case Study: Adam Frisch: How to Put a “Safe R” Seat Into Play

Brand differentiation is what enabled Joe Manchin to distance himself from the Democratic Party’s national brand and win re-election in 2018 in a state Donald Trump carried by more than 40 points just two years earlier. As much as progressives love to hate on Manchin, without him there’s no Inflation Reduction Act and perhaps no Biden resurgence in late 2022 either.

A 2022 pre-midterm poll conducted by Third Way, WelcomePAC, and Impact Research found that the Democratic brand is underwater with a majority of voters (especially swing voters) nationwide. In an era where the party’s brand is so far in the gutter, brand-differentiated candidates like Frisch and Manchin are the Democrats’ key to winning in the swing and reddish districts and states that decide control of government. Only with enough brand-differentiated candidates representing the Democrats on the front lines will the party’s brand itself begin to improve.

In other words, it will take more Manchins and Frisches for Democrats to build a sustainable majority in either House or Senate as well as mitigate future losses.

Learn More:

The Real Math on Moderation by Lauren Harper (The Bulwark)

Moderation and Electoral Overperformance by Lakshya Jain (Split Ticket)

Red Wave, Right Lessons (The Welcome Party)

The Strongest House Candidates In 2020 Were (Mostly) Moderate by Nathaniel Rakich (FiveThirtyEight)

Reaching Escape Velocity (The Welcome Party)

Overcoming the Democratic Party Brand by Aliza Astrow and Lanae Erickson (Third Way)

5. The Democratic fundraising ecosystem is broken.

The current political marketplace leads to a highly inefficient allocation of Democratic resources.

Take what happened in GA-14 in 2022 as an example. Majorie Taylor Greene’s leading challenger, Marcus Flowers, ran a glitzy digital campaign and was showered with millions in online donations. With nearly $17 million raised across the cycle, Flowers was one of the highest congressional fundraisers in the country. (Side note: Mark Zuckerberg has benefitted distinctly from Flowers’ online success: almost $4 million of the campaign’s expenditures went directly to Facebook for more fundraising advertisements.)

But due to egregious partisan gerrymandering, Democrats were doomed to lose GA-14 from the start.

In an October 2021 report for Slate, Ben Mathis-Lilley exposed this absurdity and was blunt about Flowers’ chances of beating Greene: “Flowers’ 0.00 percent chance of winning his race isn’t mentioned on his pages for the well-known ActBlue or VoteVets donor platforms, nor is it mentioned in the online advertising that Democratic firms like Run the World Digital have been paid to do on his behalf.”

Lauren Harper went further in The Bulwark, explaining how Democrats could be sending their money to candidates running in far more winnable districts:

“It’s nice to dream about beating QAnon Space Laser Lady. It would be better to actually defeat Ken Calvert—a little-known Republican incumbent whose Southern California district Trump won with just 50 percent. You save democracy with actual wins; not fantasies.”

Of course, Flowers lost by more than 30 points in November.

What’s going on here? Why did so many Democrats torch their money giving to a candidate who couldn’t possibly win?

The political scientist Eitan Hersh coined the term “rage donating” to describe the phenomenon by which hordes of online donors — many of whom gamble on politics like it’s a sport — shower gobs of money on long-shot candidates and campaigns. In his observation, the act of rage donating is far more expressive than it is impactful:

“Online giving, large and small, suffers from a problem of discipline. Rather than stopping and thinking and planning a strategy—which candidate or organization would make the best use of my money?—many online donors are just acting expressively. They see an inspiring video, and they click Donate. They see a good politician take down a bad politician in a debate or in a congressional hearing, and they click Donate. They mourn the loss of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and they click Donate. Sometimes this money goes to a great campaign or organization that will use it well. Other times, not so much.”

Rage donating has proven itself as a highly effective and reliable means of raising money in a media environment that rewards outrage and conflict. In this supercharged context, the act of donating in response can feel cathartic — a sense of instant gratification. Democrats donate to unwinnable campaigns against most-hated Republicans quite simply because it feels good.

Democratic donors have proven time and time again that they are not efficient allocators of precious resources.

WelcomePAC has documented this problem and shown how it extends across the board to dozens of winnable districts. For example, in at least 17 undervalued districts WelcomePAC identified throughout the 2022 cycle, Democrats lost without putting up a fight. Candidates running in these districts were funded at less than $1 million across the entire 2022 cycle, and often less than $200,000. In three of the four WelcomePAC-indentified districts where they did compete, Democrats did surprisingly well: one seat flipped, another was so close it went to a recount, and one was rated the third-highest overperformance of any Democratic challenger.

If Democrats are going to win in 2024 and defend our democracy, we must invest diligently in the districts with the highest ROI — not just those that make us feel good.

Learn More:

Democracy Conceded (WelcomePAC)

The Worst Investors (The Welcome Party)

Democratic Donors Are Getting Bamboozled by Lauren Harper (The Bulwark)

Interrupting the Rage Cycle (The Welcome Party)

Beware This Year’s Biggest Democratic Distraction (The Welcome Party)

But Don’t the Democrats Do That? (The Welcome Party)

‘What the hell are we doing?’: Democrats are letting beatable election-denying Republicans cruise to reelection by David Scharfenberg (The Boston Globe)

5. Democrats are facing down a future with as few as 44 Senate seats.

What does the future hold for Democrats if there’s not a coordinated effort to build a differentiated, moderate faction within the party?

Several smart political analysts have built models that show just how challenging the road ahead is for Democrats, particularly in the Senate. In 2022, Democrats were lucky to pick up a Senate seat and keep their losses narrower than expected in the House. But the road only gets harder in 2024.

Here are the seats Democrats will be forced to defend next cycle, along with their Biden 2020 vote margin (courtesy of Simon Bazelon):

Jon Tester in Montana (Biden -16.3)

Joe Manchin in West Virginia (Biden -29.9)

Sherrod Brown in Ohio (Biden -8)

Bob Casey in Pennsylvania (Biden +1.2)

Tammy Baldwin in Wisconsin (Biden +0.7)

Kyrsten Sinema in Arizona (Biden +0.3)

According to a model built by analyst David Shor, if 2024 is simply a normal year (in which Democrats win 51% of the two-party vote), they will lose seven Senate seats compared with where they are today.

Let’s caveat: yes, there are assumptions baked into this model that may not be true. Democrats may over-perform their historical averages (perhaps because Donald Trump could be the Republican nominee again). But consider the opposite scenario: Democrats could also fare worse than their historical average. What does the Senate look like in that scenario?

The point is this: Democrats need a strategy to hold onto Senate seats that will be immensely challenging to win given increasing polarization. Every year, the number of Democrats representing red states dwindles. We can’t afford to have it shrink any further.

Learn More:

David Shor Is Telling Democrats What They Don’t Want to Hear by Ezra Klein (The New York Times)

Democrats are sleepwalking into a Senate disaster by Simon Bazelon (Slow Boring)